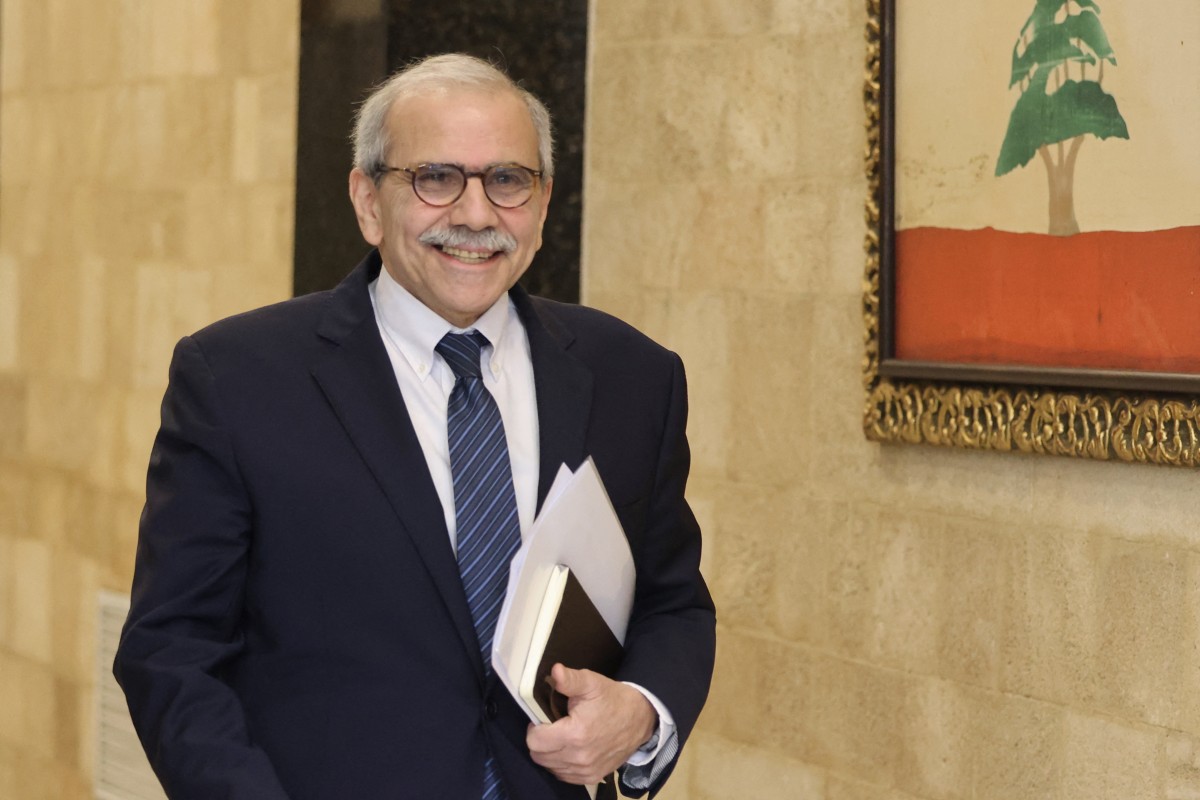

A brief yet striking statement by Prime Minister Nawaf Salam during the last Cabinet session—where Karim Souaïd was appointed Governor of the Central Bank by a vote—has largely flown under the radar.

As the session wrapped up, Salam opened a piece of paper and read: “It is known that Mr. Souaïd was not my candidate for a number of reasons, including my commitment to safeguarding depositors’ rights and preserving state assets. I, along with several ministers, expressed reservations about his appointment. However, what matters now is that the Governor—whoever he is—must from this day forward adhere to our government's financial reform policy.”

The implications of this statement are significant. By tying his reservations to concerns over depositors’ rights and public assets, is the Prime Minister suggesting that the new Central Bank Governor might not be committed to protecting either?

Even more concerning is the fact that Souaïd’s appointment passed through a Cabinet vote—garnering support from two-thirds of the ministers, reportedly in line with the President’s preferences. Does that mean those who voted in favor also lack concern for depositors and state assets?

Salam’s words carry weight. Perhaps he didn’t intend them literally. Perhaps he misspoke. But either way, his remarks warrant clarification—if not justification.

More troubling still is the vague reference to “a number of reasons.” The Prime Minister revealed two—depositors’ rights and state assets—but what about the others? Why the secrecy?

And what of the other candidates? Many of them are highly qualified and experienced. What makes Jihad Azour fundamentally different from Karim Souaïd or Eddy Gemayel, or the other names that were excluded in earlier rounds? The options for financial reform are well known. Lebanon won’t be inventing a new model—it simply needs to choose from among a narrow field of tried and tested frameworks.

No responsible official in this era would openly accept compromising depositors' rights or selling off public assets. But if we’ve learned anything from past mistakes, it’s that Lebanon’s crises—from implementing a ceasefire, to reforming governance, to restructuring public debt and returning depositors’ funds—require more than good intentions. As Prime Minister Salam put it, this is ultimately about rebuilding the state.

These are not short-term goals. They demand time—and most importantly—external support. Without international cooperation, Lebanon cannot resolve its debt crisis, nor can it shelter and repatriate its displaced citizens, many of whom come from villages in need of rebuilding.

The previous presidential term was a prime example of high activity with little to show for it. The former president and his aides proposed plans, launched initiatives, and announced projects—but none of them delivered real outcomes.

Lebanon must work with the international community to overcome its crises. And unless the world has confidence in Lebanon’s officials—their competence, integrity, intentions, and policies—it will not even bother to offer advice, let alone assistance.

Still, credit must be given where it's due: the Prime Minister’s transparency, and his insistence that all appointees serve under the government’s directives in the public interest, are worth noting. Whether it was a calculated reveal or a rhetorical stumble, it shed light on the complex power dynamics shaping Lebanon’s financial future.

French

French